Command Line 101

How to Work in a Text-Only Environment.

What is this thing?

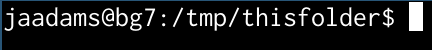

When you first open a command-line (note that I use the terms command-line and shell interchangably here, they’re basically the same, but command-line is the more general term, and shell is the name for the program that executes commands for you) you’ll see something like this:

This line is called a “command prompt” and it tells you four pieces of information:

jaadams: The username of the user that is currently running this shell.bg7: The name of the computer that this shell is running on, important for when you start accessing shells on remote machines./tmp/thisfolder: The folder or directory that your shell is currently running in. Like a file explorer (like Window’s Explorer or Mac’s Finder) a shell always has a “working directory,” from which all relative paths (see sidenote below) are resolved.

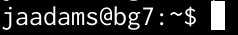

When you first opened a shell, however, you might notice that is looks more like this:

This is a shorthand notation that the shell uses to make this output shorter

when possible. ~ stands for your home directory, usually /home/<username>.

Like C:\Users\<username>\ on Windows or /Users/<username> on Mac,

this directory is where all your files should go by default.

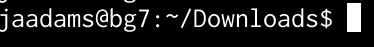

Thus a command prompt like this:

actually tells you that you are currently in the /home/jaadams/Downloads

directory.

Sidenote: The Unix Filesystem and Relative Paths

“folders” on Linux and other Unix-derived systems like MacOS are usually called “directories.”

These directories are represented by paths, strings that indicate where the directory is on the filesystem.

The one unusual part is the so-called “root directory”.

All files are stored in this folder or directories under it.

Its path is just / and there are no directories above it.

For example, the directory called home typically contains all user directories.

This is stored in the root directory, and each users specific data

is stored in a directory named after that user under home.

Thus, the home directory of the user jacob is typically /home/jacob,

the directory jacob under the

home directory stored in the root directory /.

If you’re interested in more details about what goes in what directory,

man hier has the basics and the

Filesystem Hierarchy Standard

governs the layout of the filesystem on most Linux distributions.

You don’t always have to use the full path, however.

If the path does not begin with a /, it is assumed that the path actually

begins with the path of the current directory.

So if you use a path like my/folders/here, and you’re in the /home/jacob

directory, the path will be treated like /home/jacob/my/folders/here.

Each folder also contains the symbolic links .. and ..

Symbolic links are a very powerful kind of

file that is actually a reference to another file.

.. always represents the parent directory

of the current directory, so /home/jacob/.. links to /home/.

. always links to the current directory, so /home/jacob/. links to

/home/jacob.

Running commands

To run a command from the command prompt, you type its name and then usually some arguments to tell it what to do.

For example, the echo command displays the text passed as arguments.

jacob@lovelace/home/jacob$ echo hello world

hello world

Arguments to commands are space-separated, so in the previous example hello

is the first argument and world is the second. If you need an argument to

contain spaces, you’ll want to put quotes around it, echo "like so".

Certain arguments are called “flags”, or “options” (options if they take another argument, flags otherwise) usually prefixed with a hyphen, and they change the way a program operates.

For example, the ls command outputs the contents of a directory passed as

an argument, but if you add -l before the directory, it will give you more

details on the files in that directory.

jacob@lovelace/tmp/test$ ls /tmp/test

1 2 3 4 5 6

jacob@lovelace/tmp/test$ ls -l /tmp/test

total 0

-rw-r--r-- 1 jacob jacob 0 Aug 26 22:06 1

-rw-r--r-- 1 jacob jacob 0 Aug 26 22:06 2

-rw-r--r-- 1 jacob jacob 0 Aug 26 22:06 3

-rw-r--r-- 1 jacob jacob 0 Aug 26 22:06 4

-rw-r--r-- 1 jacob jacob 0 Aug 26 22:06 5

-rw-r--r-- 1 jacob jacob 0 Aug 26 22:06 6

jacob@lovelace/tmp/test$

Most commands take different flags to change their behavior in various ways.

File Management

cd <path>: Change the current directory of the running shell to<path>.ls <path>: Output the contents of<path>. If no path is passed, it prints the contents of the current directory.touch <filename>: create an new empty file called<filename>. Used on an existing file, it updates the file’s last accessed and modified times. Most text editors can also create a new file for you, which is probably more useful.mkdir <directory>: Create a new folder/directory at path<directory>.mv <src> <dest>: Move a file or directory at path<src>to<dest>.cp <src> <dest>: Copy a file or directory at path<src>to<dest>.rm <file>: Remove a file at path<file>.zip -r <zipfile> <contents...>: Create a zip file<zipfile>with contents<contents>.<contents>can be multiple arguments, and you’ll usually want to use the-rargument when including directories in your zipfile, as otherwise only the directory will be included and not the files and directories within it.

Searching

grep <thing> <file>: Look for the string<thing>in<file>. If no<file>is passed it searches standard input.find <path> -name <name>: Find a file or directory called<name>somwhere under<path>. This command is actually very powerful, but also very complex. For example you can delete all files in a directory older than 30 days with:find -mtime +30 -exec rm {}\;locate <name>: A much easier to use command to find a file with a given name, but it is not usually installed by default.

Outputting Files

cat <files...>: Output (concatenate) all the files passed as arguments.head <file>: Output the beginning of<file>tail <file>: Output the end of<file>

How to Find the Right Command

All commands (at least on sane Linux distributions like Debian or Ubuntu)

are documented with a manual page, in man section 1 (for more information on

manual sections, run man intro).

This can be accessed using man <command>

You can search for the right command using the -k flag, as in man -k <search>.

You can also view manual pages in your browser, on sites like https://manpages.debian.org or https://linux.die.net/man.

This is not always helpful, however, because some command’s descriptions are

not particularly useful, and also there are a lot of manual pages, which can

make searching for a specific one difficult. For example, finding the right

command to search inside text files is quite difficult via man (it’s grep).

When you can’t find what you need with man I recommend falling back to

searching the Internet. There are lots of bad Linux tutorials out there, but

here are some reputable sources I recommend:

- https://www.cyberciti.biz: nixCraft has excellent tutorials on all things Linux

- Hosting providers like Digital Ocean or Linode: Good intro documentation, but can sometimes be outdated

- https://tldp.org: The Linux Documentation project is great, but it can also be a little outdated sometimes.

- https://stackoverflow.com: Oftentimes has great answers, but quality varies wildly since anyone can answer.

These are certainly not the only options but they’re the sources I would recommend when available.

How to Read a Manual Page

Manual pages consist of a series of sections, each with a specific purpose. Instead of attempting to write my own description here, I’m going to borrow the excellent one from The Linux Documentation Project

The NAME section

…is the only required section. Man pages without a name section are as useful as refrigerators at the north pole. This section also has a standardized format consisting of a comma-separated list of program or function names, followed by a dash, followed by a short (usually one line) description of the functionality the program (or function, or file) is supposed to provide. By means of makewhatis(8), the name sections make it into the whatis database files. Makewhatis is the reason the name section must exist, and why it must adhere to the format I described. (Formatting explanation cut for brevity)

The SYNOPSIS section

…is intended to give a short overview on available program options. For functions this sections lists corresponding include files and the prototype so the programmer knows the type and number of arguments as well as the return type.

The DESCRIPTION section

…eloquently explains why your sequence of 0s and 1s is worth anything at all. Here’s where you write down all your knowledge. This is the Hall Of Fame. Win other programmers’ and users’ admiration by making this section the source of reliable and detailed information. Explain what the arguments are for, the file format, what algorithms do the dirty jobs.

The OPTIONS section

…gives a description of how each option affects program behaviour. You knew that, didn’t you?

The FILES section

…lists files the program or function uses. For example, it lists configuration files, startup files, and files the program directly operates on. (Cut details about installing files)

The ENVIRONMENT section

…lists all environment variables that affect your program or function and tells how, of course. Most commonly the variables will hold pathnames, filenames or default options.

The DIAGNOSTICS section

…should give an overview of the most common error messages from your program and how to cope with them. There’s no need to explain system error error messages (from perror(3)) or fatal signals (from psignal(3)) as they can appear during execution of any program.

The BUGS section

…should ideally be non-existent. If you’re brave, you can describe here the limitations, known inconveniences and features that others may regard as misfeatures. If you’re not so brave, rename it the TO DO section ;-)

The AUTHOR section

…is nice to have in case there are gross errors in the documentation or program behaviour (Bzzt!) and you want to mail a bug report.

The SEE ALSO section

…is a list of related man pages in alphabetical order. Conventionally, it is the last section.

Remote Access

One of the more powerful uses of the shell is through ssh, the secure shell.

This allows you to remotely connect to another computer and run a shell on that

machine:

user@host:~$ ssh other@example.com

other@example:~$

The prompt changes to reflect the change in user and host, as you can see in the example above. This allows you to work in a shell on that machine as if it was right in front of you.

Moving Files Between Machines

There are several ways you can move files between machines over ssh.

The first and easiest is scp, which works much like the cp command

except that paths can also take a user@host argument to move files across

computers. For example, if you wanted to move a file test.txt to your

home directory on another machine, the command would look like:

scp test.txt other@example.com:

(The home directory is the default path)

Otherwise you can move files by reversing the order of the arguments

and put a path after the colon to move files from another directory on the

remote host. For example, if you wanted to fetch the file /etc/issue.net

from example.com:

scp other@example.com:/etc/issue.net .

Another option is the sftp command, which gives you a very simple shell-like

interface in which you can cd and ls, before either puting files onto

the local machine or geting files off of it.

The final and most powerful option is rsync which syncs the contents of one

directory to another, and doesn’t copy files that haven’t changed. It’s powerful

and complex, however, so I recommend reading the USAGE section of its man page.

Long-Running Commands

The one problem with ssh is that it will stop any command running in your shell when you disconnect. If you want to leave something on and come back later then this can be a problem.

This is where terminal multiplexers come in. tmux and screen both allow

you to run a shell in a safe environment where it will continue even if you

disconnect from it. You do this by running the command without any arguments,

i.e. just tmux or just screen.

In tmux you can disconnect from the current session by

pressing Ctrl+b then d, and reattach with the tmux attach command.

screen works similarly, but with Ctrl+a instead of b and screen -r to

reattach.

Command Inputs and Outputs

Arguments are not the only way to pass input to a command. They can also take input from what’s called “standard input”, which the shell usually connects to your keyboard.

Output can go to two places, standard output and standard error, both of which are directed to the screen by default.

Redirecting I/O

Note that I said above that standard input/output/error are only “usually”

connected to the keyboard and the terminal? This is because you can redirect

them to other places with the shell operators <, > and the very powerful |.

File redirects

The operators < and > redirect the input and output of a command to a file.

For example, if you wanted a file called list.txt that contained a list of

all the files in a directory /this/one/here you could use:

ls /this/one/here > list.txt

Pipelines

The pipe character, |, allows you to direct the output of one command into

the input of another. This can be very powerful.

For example, the following pipeline lists the contents of the current directory

searches for the string “test”, then counts the number of results.

(wc -l counts the number of lines in its input)

ls | grep test | wc -l

For a better, but even more contrived example, say you have a file myfile,

with a bunch of lines of potentially duplicated and unsorted data

test

test

1234

4567

1234

You can sort it and output only the unique lines with sort and uniq:

$ uniq < myfile | sort

1234

1234

4567

test

Save Yourself Some Typing: Globs and Tab-Completion

Sometimes you don’t want to type out the whole filename when writing out a command. The shell can help you here by autocompleting when you press the tab key.

If you have a whole bunch of files with the same suffix, you can refer to them

when writing arguments as *.suffix. This also works with prefixes, prefix*,

and in fact you can put a * anywhere, *middle*. The shell will “expand” that

* into all the files in that directory that match your criteria

(ending with a specific suffix, starting with a specific prefix, and so on)

and pass each file as a separate argument to the command.

For example, if I have a series of files called 1.txt, 2.txt, and so on

up to 9, each containing just the number for which it’s named, I could use

cat to output all of them like so:

jacob@lovelace/tmp/numbers$ ls

1.txt 2.txt 3.txt 4.txt 5.txt 6.txt 7.txt 8.txt 9.txt

jacob@lovelace/tmp/numbers$ cat *.txt

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Also the ~ shorthand mentioned above that refers to your home directory

can be used when passing a path as an argument to a command.

Ifs and For loops

The files in the above example were generated with the following shell commands:

for i in 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

do

echo $i > $i.txt

done

But I’ll have to save variables, conditionals and loops for another day because this is already too long. Needless to say the shell is a full programming language, although a very ugly and dangerous one.