Roman Finger Counting

I recently wrote a final paper on the history of written numerals. In the process, I discovered this fascinating tidbit that didn’t really fit in my paper, but I wanted to put it somewhere. So I’m writing about it here.

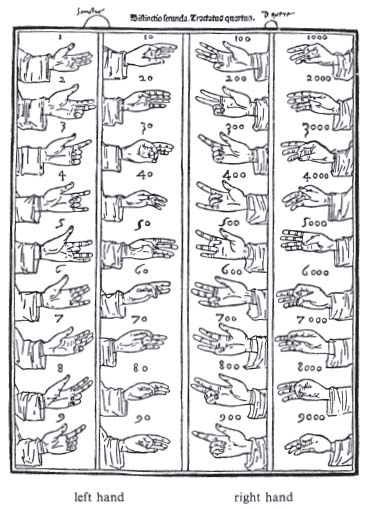

If I were to ask you to count as high as you could on your fingers you’d probably get up to 10 before running out of fingers. You can’t count any higher than the number of fingers you have, right? The Romans could! They used a place-value system, combined with various gestures to count all the way up to 9,999 on two hands.

The System

(Note that in this diagram 60 is, in fact, wrong,

and this picture swaps the hundreds and the thousands.)

(Note that in this diagram 60 is, in fact, wrong,

and this picture swaps the hundreds and the thousands.)

We’ll start with the units. The last three fingers of the left hand, middle, ring, and pinkie, are used to form them.

Zero is formed with an open hand, the opposite of the finger counting we’re used to.

One is formed by bending the middle joint of the pinkie, two by including the ring finger and three by including the middle finger, all at the middle joint. You’ll want to keep all these bends fairly loose, as otherwise these numbers can get quite uncomfortable. For four, you extend your pinkie again, for five, also raise your ring finger, and for six, you raise your middle finger as well, but then lower your ring finger.

For seven you bend your pinkie at the bottom joint, for eight adding your ring finger, and for nine, including your middle finger. This mirrors what you did for one, two and three, but bending the finger at the bottom joint now instead.

This leaves your thumb and index finger for the tens. For ten, touch the nail of your index finger to the inside of your top thumb joint. For twenty, put your thumb between your index and middle fingers. For thirty, touch the nails of your thumb and index fingers. For forty, bend your index finger slightly towards your palm and place your thumb between the middle and top knuckle of your index finger. For fifty, place your thumb against your palm. For sixty, leave your thumb where it is and wrap your index finger around it (the diagram above is wrong). For seventy, move your thumb so that the nail touches between the middle and top knuckle of your index finger. For eighty, flip your thumb so that the bottom of it now touches the spot between the middle and top knuckle of your index finger. For ninety, touch the nail of your index finger to your bottom thumb joint.

The hundreds and thousands use the same positions on the right hand, with the units being the thousands and the tens being the hundreds. One account, from which the picture above comes, swaps these two, but the first account we have uses this ordering.

Combining all these symbols, you can count all the way to 9,999 yourself on just two hands. Try it!

History

The Venerable Bede

The first written record of this system comes from the Venerable Bede, an English Benedictine monk who died in 735.

He wrote De computo vel loquela digitorum, “On Calculating and Speaking with the Fingers,” as the introduction to a larger work on chronology, De temporum ratione. (The primary calculation done by monks at the time was calculating the date of Easter, the first Sunday after the first full moon of spring).

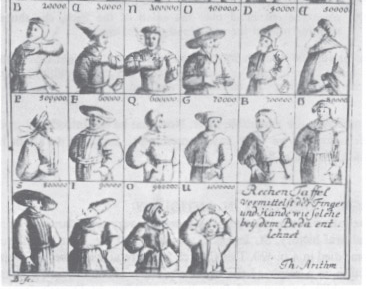

He also includes numbers from 10,000 to 1,000,000, but its unknown if these were inventions of the author and were likely rarely used regardless. They require moving your hands to various positions on your body, as illustrated below, from Jacob Leupold’s Theatrum Arilhmetico-Geometricum, published in 1727:

The Romans

If Bede was the first to write it, how do we know that it came from Roman times? It’s referenced in many Roman writings, including this bit from the Roman satirist Juvenal who died in 130:

Felix nimirum qui tot per saecula mortem distulit atque suos iam dextera computat annos.

Happy is he who so many times over the years has cheated death And now reckons his age on the right hand.

Because of course the right hand is where one counts hundreds!

There’s also this Roman riddle:

Nunc mihi iam credas fieri quod posse negatur: octo tenes manibus, si me monstrante magistro sublatis septem reliqui tibi sex remanebunt.

Now you shall believe what you would deny could be done: In your hands you hold eight, as my teacher once taught; Take away seven, and six still remain.

If you form eight with this system and then remove the symbol for seven, you get the symbol for six!

Sources

My source for this blog post is Paul Broneer’s 1969 English translation of Karl Menninger’s Zahlwort und Ziffer (Number Words and Number Symbols).